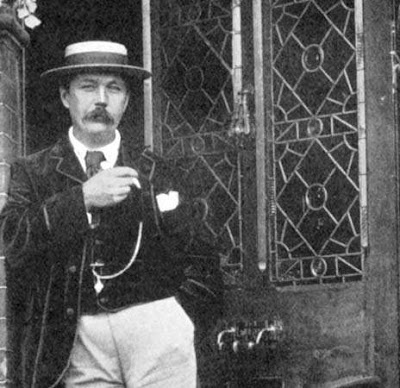

The Father Of Sherlock Holmes: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Biography

Arthur Conan Doyle, in full Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle, (born May 22, 1859, Edinburgh, Scotland—died July 7, 1930, Crowborough, Sussex, England), Scottish writer best known for his creation of the detective Sherlock Holmes—one of the most vivid and enduring characters in English fiction.

Conan Doyle, the second of Charles Altamont and Mary Foley Doyle’s 10 children, began seven years of Jesuit education in Lancashire, England, in 1868. After an additional year of schooling in Feldkirch, Austria, Conan Doyle returned to Edinburgh. Through the influence of Dr. Bryan Charles Waller, his mother’s lodger, he prepared for entry into the University of Edinburgh’s Medical School. He received Bachelor of Medicine and Master of Surgery qualifications from Edinburgh in 1881 and an M.D. in 1885 upon completing his thesis, “An Essay upon the Vasomotor Changes in Tabes Dorsalis".

Mary Doyle had a passion for books and was a master storyteller. Her son Arthur wrote of his mother's gift of "sinking her voice to a horror-stricken whisper" when she reached the culminating point of a story. There was little money in the family and even less harmony on account of his father's excesses and erratic behaviour. Arthur's touching description of his mother's beneficial influence is also poignantly described in his autobiography, "In my early childhood, as far as I can remember anything at all, the vivid stories she would tell me stand out so clearly that they obscure the real facts of my life."

Charles Altamont Doyle, Arthur's father, a chronic alcoholic, was a moderately successful artist, who apart from fathering a brilliant son, never accomplished anything of note. At the age of twenty-two, Charles had married Mary Foley, a vivacious and well educated young woman of seventeen.

After Arthur reached his ninth birthday, the wealthy members of the Doyle family offered to pay for his studies. He was in tears all the way to England, where he spent seven years in a Jesuit boarding school. Arthur loathed the bigotry surrounding his studies and rebelled at corporal punishment, which was prevalent and incredibly brutal in most English schools of that epoch.

During those gruelling years, Arthur's only moments of happiness were when he wrote to his mother, a regular habit that lasted for the rest of her life, and also when he practised sports, mainly cricket, at which he was very good. It was during these difficult years at boarding school that Arthur realized he also had a talent for storytelling. He was often found surrounded by a bevy of totally enraptured younger students listening to the amazing stories he would make up to amuse them.

By 1876, graduating at the age of seventeen, Arthur Doyle, (as he was called, before adding his middle name "Conan" to his surname), was a surprisingly normal young man. With his innate sense of humour and his sportsmanship, having ruled out any feelings of self-pity, Arthur was ready and willing to face the world.

While a medical student, Conan Doyle was deeply impressed by the skill of his professor, Dr. Joseph Bell, in observing the most minute detail regarding a patient’s condition.

Without much enthusiasm, Conan Doyle returned to his studies in the autumn of 1880. A year later, he obtained his "Bachelor of Medicine and Master of Surgery degree. On this occasion, he drew a humorous sketch of himself receiving his diploma, with the caption: "Licensed to Kill”.

He moved around southern England until he finally settled in the town of Southsea. Doyle had written for his own pleasure up until this point in his life but succeeded in publishing A Study in Scarlet in 1887, a slim novel that introduced the world to Sherlock Holmes.

Doyle wrote another Sherlock Holmes novel, The Sign of Four, in 1890, and moved with his wife, Louise, to London in 1891. By this time, Doyle had decided to become an eye doctor. (His first two Sherlock Holmes novels had not been financial successes.) Ironically, however, Doyle found that he had few patients and was consequently left with plenty of time to write. By switching formats and writing Holmes mysteries as short stories rather than novels, Doyle was able to capitalize on his talent for writing rapid, engrossing plots and minimize some of the tedium that had plagued his earlier work. Serialized in the popular magazine, the Strand, Sherlock Holmes and his adventures became an overnight phenomenon, electrifying readers throughout the English-speaking world. “The Red-Headed League” first appeared in the Strand in 1891 and was published a year later with eleven other stories as The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes.

In a matter of months, Doyle went from a struggling eye doctor to one of the most famous writers in the world. He quickly grew tired of being solely identified with Holmes. In 1893, he killed off his fictional detective in a climactic battle with the evil Professor Moriarity. Readers in Britain and the United States mourned the loss of their hero, and grown men were seen to wear black armbands for weeks afterward.

Doyle continued to write both fiction and nonfiction throughout the 1890s, although none of his works were as popular as the Sherlock Holmes stories. Hoping to boost his popularity and sales, Doyle revived Sherlock Holmes again in 1901 with The Hound of the Baskervilles, a novel many critics regard as one of the greatest mysteries ever written. In 1903, he began writing Holmes stories again and continued to do so almost until his death in 1930. In addition to many other works, he published The Lost World, a popular science-fiction novel, in 1912.

The Sherlock Holmes Museum, Baker Street, London.

The success of the Sherlock Holmes stories can hardly be overstated. Almost single-handedly, Doyle inaugurated two massive changes in literature. First, he transformed the short story from a mildly successful exercise to a major literary form capable of sustaining both an enormous readership and a longstanding critical interest. Second, Doyle perfected and popularized the detective story, which went on to become the most popular new genre of fiction in the twentieth century. Previous writers such as Edgar Allen Poe had published short stories and mysteries before, but all had failed to energize readers to the degree that Doyle’s Holmes energized them. Readers also identified with Holmes’s real-world London and liked the fact that they had the opportunity to solve the mysteries along with the hero. Sherlock Holmes had become so popular that by the end of the twentieth century he’d appeared in more than 100 films, more than 700 radio dramas, and more than 2,000 stories and novels. Perhaps only Mickey Mouse rivals Holmes as the most recognizable fictional character of the past century.

The Sherlock Holmes Museum: Cluttered bookshelves in Sherlock's Study

Much of Doyle’s popularity today stems from his vivid description of late-Victorian London. From the defeat of Napoleon in 1815 to the start of World War I in 1914, Britain was the dominant military power in the world. As a result, London was both the world’s largest city and the center of the most extensive and powerful empire in history by the end of the nineteenth century. Victorian London was also a city of mystery: a place of dark fogs, horse-drawn carriages, and Jack the Ripper. In other words, even though London at the end of the nineteenth century was the de facto capital of the world, Londoners were still deeply interested in their city’s dark undercurrents. Readers today find this mix of power and mystery fascinating and share with Doyle’s contemporaries a love for the way in which the intellect of Sherlock Holmes cuts through the shadows, illuminating the darkness with pure reason.

This master of diagnostic deduction became the model for Conan Doyle’s literary creation, Sherlock Holmes, who first appeared in A Study in Scarlet, a novel-length story published in Beeton’s Christmas Annual of 1887. Other aspects of Conan Doyle’s medical education and experiences appear in his semiautobiographical novels, The Firm of Girdlestone (1890) and The Stark Munro Letters (1895), and in the collection of medical short stories Round the Red Lamp (1894).

Conan Doyle’s creation of the logical, cold, calculating Holmes, the “world’s first and only consulting detective,” sharply contrasted with the paranormal beliefs Conan Doyle addressed in a short novel of this period, The Mystery of Cloomber (1889). Conan Doyle’s early interest in both scientifically supportable evidence and certain paranormal phenomena exemplified the complex diametrically opposing beliefs he struggled with throughout his life.

Sherlock Holmes Statue, Edinburgh, located near the birthplace and childhood home of Arthur Conan Doyle.

Conan Doyle married Louisa Hawkins in 1885, and together they had two children, Mary and Kingsley. A year after Louisa’s death in 1906, he married Jean Leckie and with her had three children, Denis, Adrian, and Jean. Conan Doyle was knighted in 1902 for his work with a field hospital in Bloemfontein, South Africa, and other services during the South African (Boer) War.

Conan Doyle died in Windlesham, his home in Crowborough, Sussex, and at his funeral his family and members of the spiritualist community celebrated rather than mourned the occasion of his passing beyond the veil. On July 13, 1930, thousands of people filled London’s Royal Albert Hall for a séance during which Estelle Roberts, the spiritualist medium, claimed to have contacted Sir Arthur.

Conan Doyle detailed what he valued most in life in his autobiography, Memories and Adventures (1924), and the importance that books held for him in Through the Magic Door (1907).

The Sherlock Holmes Museum, London

References:

1. https://www.arthurconandoyle.com/biography.html

2. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Arthur-Conan-Doyle

3. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Arthur-Conan-Doyle

Comments

Post a Comment